Before you start reading this article, have you read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 in the series?

Periodization is perhaps the most important, yet most often neglected component of a fighters’ training plan. Periodization is the process of organizing your training plan over a period of time to help you manage your fatigue on a daily, weekly and monthly basis. It is hoped that this will reduce your potential for over-training and optimize your performance in the cage on fight day.

Periodization is a blend of art and science. On the artistic side, it is a subjective organizational tool that helps you divide your training into specific periods that manipulate volume and intensity, so as to minimise fatigue and over-training, and maximise your performance at some future date. On the Scientific side, numerous studies have shown that periodized training plans result in superior strength, power and endurance gains across genders, both in trained and untrained groups, and in young and old populations, compared to non-periodized training plans.

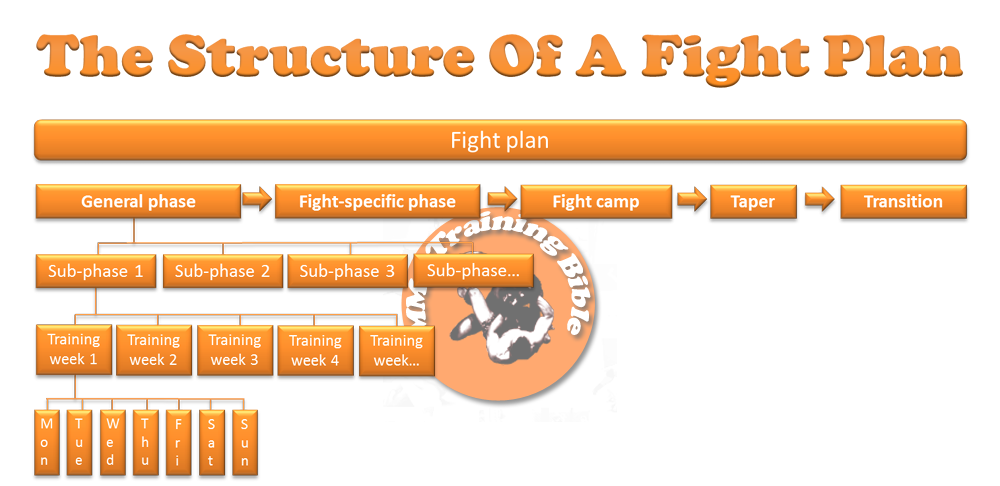

I hope you can see the importance of taking a structured approach to developing your fight plan. The MMA Training Bible does this by dividing a fighters training plan into smaller periods with very specific objectives that differ depending upon the phase of training that they are in. This approach (shown below) helps you manage your fatigue on a daily, weekly and monthly basis, which will optimise your adaptations to training and improve your performance on fight day.

The first thing to notice about the fight plan shown above is that it’s divided into a number of large phases: the general preparation phase, the fight-specific preparation phase, the fight camp, taper, and transition. Each of these big training phases is further divided into smaller sub-phases that are carefully organised to help you manage your fatigue on a monthly basis. Each sub-phase is further divided into training weeks, which help you manage your fatigue on a weekly basis. Training weeks are further divided into training days, which can be further divided into any number of training sessions. Below we’ll take a look at each phase in a bit more detail, but if you want to really study this concept, I suggest you check out this article series on Periodization.

Training phases

You’re always going to structure your fight plan into a few large phases, no matter how many times you fight in one year, they are 1) The general preparation phase, 2) The fight-specific preparation phase, 3) The fight camp, 4) The taper, 5) The transition. Each phase has very specific objectives. Let’s take a deeper look at each of these phases.

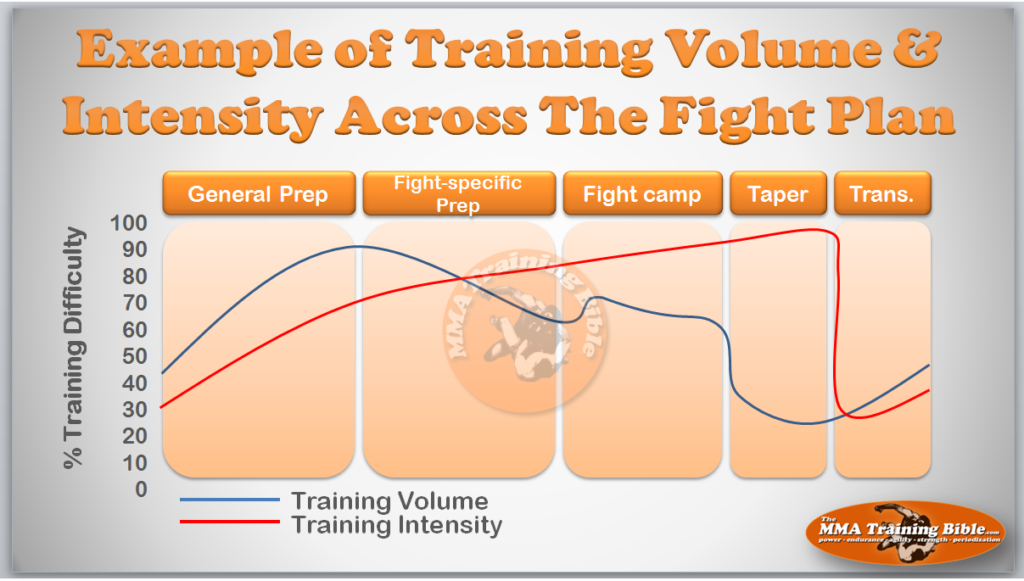

The main objective of the general preparation phase is to establish a high level of physical conditioning by using large volumes of general and non-specific MMA activities. This should include the development of high intensity aerobic endurance and a foundation of strength in a wide variety of activities. Any needed changes in body composition should also be addressed during this phase. The general preparation phase should be longer for beginner and intermediate fighters, and shorter for more advanced fighters (in some special cases, it can be eliminated altogether). Because the main emphasis is on increasing training volume, your level of fatigue will increase, so competitions should not be scheduled in this phase.

Like the general preparation phase, the fight-specific phase aims to improve aerobic endurance and strength, but rather than using general exercises like running, cycling or rowing to achieve this, more fight-specific drills are incorporated. Training volume decreases throughout this phase, which allows for a gradual increase in training intensity. About mid-way through this phase, training intensity may surpass volume. As your training becomes more specific to MMA, you become more prepared to fight. In the later part of this phase, competitions can be used to provide feedback about a fighter’s exact level of preparedness, but competitions should only be entered when the fighter is capable of achieving their most important training objectives. If you’re going to do this, competitions and opponents should progressively increase in difficulty as the main fight gets closer. You’ve got to be careful to minimize the risk of injury when you’re entering heavy contact competitions during this phase. If you don’t want to, then non-contact submission wrestling/jiu-jitsu or boxing/kick-boxing competitions with protective gear might be a good idea. Both the general and fight-specific preparation phases are probably the most important because they establish your physical, technical, and psychological base for the fight camp. If you skip either one, or they are inappropriately designed, your ability to tolerate high intensity training during the fight camp will be compromise, along with your fighting performance.

The main goal of the fight camp is to bring together all of the performance factors that the fighter needs to compete successfully. At this stage the fighter should be focusing on psychological training and perfecting specific techniques and tactics that will be used in the fight. At the beginning of the fight camp, training volume increases for a short period, followed by a return to normal training volumes. This increase in training volume at the beginning of the fight camp allows the fighter to place a greater emphasis on fight specific technical and tactical preparation. This period of concentrated loading is placed at the beginning of the fight camp, approximately eight to 10 weeks before the fight, because some research has shown that training adaptations from very intense periods may take many weeks to present. Training intensity continues to increase throughout the remainder of the fight camp, reaching its highest level two to three weeks prior to a fight.

In the last 8 to 14 days before your fight, a taper or unloading period should be used. The goal of a taper is to optimize your performance in the cage. This is achieved by reducing training volume while maintaining intensity for two weeks before your fight. The number of weekly training sessions should fall by about 20 %.

After your fight, a three to six week transition phase is necessary to remove the accumulated physiological and psychological fatigue that developed during the past few months of training. This phase is not an off-season, because fighters do not have an off-season, it’s a transition from one fight plan to the next.

Just to make things a little more clear for you, I’ve put together a figure showing how your training volume and intensity should change across a fight plan.

Sub-phases

In this section, we’re going to move one level down, and talk about how to organize the sub-phases. Training sub-phases typically last about four weeks. But not all sub-phases are created equal. What really makes one training sub-phase different from another training sub-phase is its difficulty and the type of loading plan it uses. For more information on these concepts, check out this article. There are actually four different types of sub-phases that the MMA Training Bible uses to help you manage your fatigue on a month-to-month basis. They are: developmental sub-phases, shock sub-phases, the tapering sub-phase and the transition sub-phase. To make sure you get this, I want to give you an example of each, so let’s start with developmental sub-phases.

Developmental sub-phases should be used throughout your entire fight plan. They progress gradually in training difficulty over a sub-phase, like a staircase, and generally achieve their highest training difficulty just before a recovery week at the end. Here is an example of a developmental sub-phase using a 3:1 loading plan. Novice/beginner fighters should start with one loading week (low training difficulty) followed by one recovery week (i.e. a loading plan of 1:1), progressing to a 2:1, 3:1 or 4:1 loading plan with training difficulty increasing in a step-wise manner. More advanced fighters can begin the general preparatory phase with more demanding loading plans (starting at medium training difficulty, using a 3:1 or 4:1 loading plan) because they should have a sufficient base of endurance and strength from previous training.

Shock sub-phases feature a sharp increase in training difficulty over one to three weeks, followed by a recovery week. Sharply increasing training difficulty every once in a while, is a useful tool for breaking through plateaus in performance, which will occur after about three weeks of training with the same loads. The adaptations that result from the sudden increase in training difficulty can appear as quickly as 10 days, but it is important to remember that the higher the training stress, the longer time it takes to dissipate the fatigue and to undergo supercompensation. It’s probably safe to say that shock sub-phases should not be used within three weeks of a fight because any positive physiological adaptation that could be gained from them wouldn’t present until after your fight anyway. Also, shock sub-phases should not be planned back-to-back, as this will most probably result in over-training. After you’ve completed your first shock sub-phase, you’ll likely plan to complete a few developmental sub-phase. Eventually, you’ll want to incorporate another shock sub-phase into your training. This time, your shock sub-phase should incorporate two training weeks that feature a sharp increase in training difficulty. Similarly, after you’ve completed your second shock sub-phase, you should complete a few developmental sub-phase. Eventually, you’ll want to incorporate another shock sub-phase into your training. This time, your shock sub-phase should incorporate three training weeks that feature a sharp increase in training difficulty. Beginners can first start to incorporate shock sub-phases at the end of the general preparatory period, after a base of endurance and strength has been developed. Intermediate/advanced fighters who have a solid base of strength can use them earlier in training. Ok, let’s move on to the taper sub-phase.

The taper sub-phase is pretty simple, you only use it before a fight, when you’re trying to peak. The taper sub-phase features a large drop in training difficulty over two weeks before the fight. Now let’s move on to the transition sub-phase.

The transition sub-phase is only used after your fight, and features a steady build-up of training difficulty over a few weeks. As a general rule, the longer the fight plan, the greater amount of time should be spent in transition; this can range from 3 to 6 weeks. The length of this sub-phase, and the training demand you choose will also depend on any injuries that you have incurred during training and/or the fight.

So, that is an overview of how and why the MMA Training Bible structures its training sub-phases the way it does. Let’s move on to discuss training weeks.

How to plan & sequence training weeks

In this section, we’re going to go down one step further and show you how to organize your training weeks. Although the training week is a small cycle (it is made up of the days of the week), it is probably the most important element of the entire fight plan because it lays out your day-to-day training schedule. It is also the most difficult to plan in advance because many unpredictable factors influence the number of days that you can train per week, from social and work/study commitments, to gym timetables and your level of fatigue. For this reason, you should not plan more than a few training weeks into the future.

There are four different types of training weeks that you should know about. They can be classified as developmental (DEV), shock (SHOCK), recovery (REC), or peaking (PEAK) (1). It is relatively straight forward to assign these training weeks to the fight plan. I want to go into a bit of detail about each of these; let’s start with recovery training weeks.

Recovery training weeks are designed to dissipate fatigue and elevate your adaptation from previous shock training sub-phases. Recover training weeks absolutely essential in helping you avoid over-training. If you’re a fighter and you’re not currently using a recovery training week, then you’re probably over-training. The recovery week has a much lower training difficulty than other weeks. Recovery training weeks typically contain training sessions that have slightly longer warm-ups, lighter workloads, and they are typically shorter in length than the training sessions of other weeks. To reduce monotony, coaches can intersperse games or fun activities, or special events into recovery training weeks. For example, beginner/intermediate fighters may play a game of basketball, or advanced fighters may instruct technical classes for beginners.

Developmental training weeks are used throughout your fight plan. Their objective is to increase the level of your physiological adaptation to training, develop technical and tactical abilities, and improve performance factors such as strength and power or aerobic and anaerobic endurance, or agility.

Shock training weeks contain a planned increase in training difficulty, which can be achieved by increasing the number of sessions per week, increasing the difficulty of the exercises (i.e. by using higher power-output exercises), and/or by increasing the volume and intensity of each workout. The whole point of the shock training week is to cause a greater level of physiological adaptation, which will improve your performance if you allow it to, by for example, taking a recovery week after it.

Taper weeks are only included in the Taper sub-phase. A taper normally takes up the 2 weeks before your fight. During the first week of the tapering period, training frequency should be maintained at around 80 % of pre-taper values in order to maintain technical proficiency. Training difficulty will fall by 40 % to 60 % over the first week, and by another 10 % to 20 % in the second week of the taper. During the taper, the fighter should incorporate several short, but high intensity training sessions that use long rest intervals in order to dissipate fatigue. The high intensity training will also help to maintain physiological adaptations from previous training. Strength training should be reduced to one or two sessions, all other session should be very low intensity, focusing on tactical preparation. The final week of the taper should feature just a few (i.e. one or two) high intensity sessions early in the week.

Finally, the transition features a combination of recovery and developmental training weeks.

Take Care,

Dr Gillis

Leave a Reply