Overtraining is one of the toughest opponents a fighter will ever face; its onset is insidious and it plays upon your fear of under-preparation. Add this to the long list of performance factors that a successful fighter must training; like strength, power, agility, an/aerobic endurance, not to mention your technical development, and you see why so many fighters burn-out before reaching their full potential.

To avoid overtraining, undertraining, injury and burn-out, you need to know what to train and when to train it. You need to know when to train hard so that you adapt and grow stronger, but you also need to know when to take a recovery day or a recovery week. The first step in all of this is about understanding how your body responds to training; that is what we shall cover in Part 1 of this article. After you have a good understanding of how your body responds to training, you than must understand what overtraining is and how to recognize the signs and symptoms of overtraining. That is what we’re going to cover in Part two of this article series. Ok, lets jump right into Part 1.

Part 1: How your body responds to the stress of training

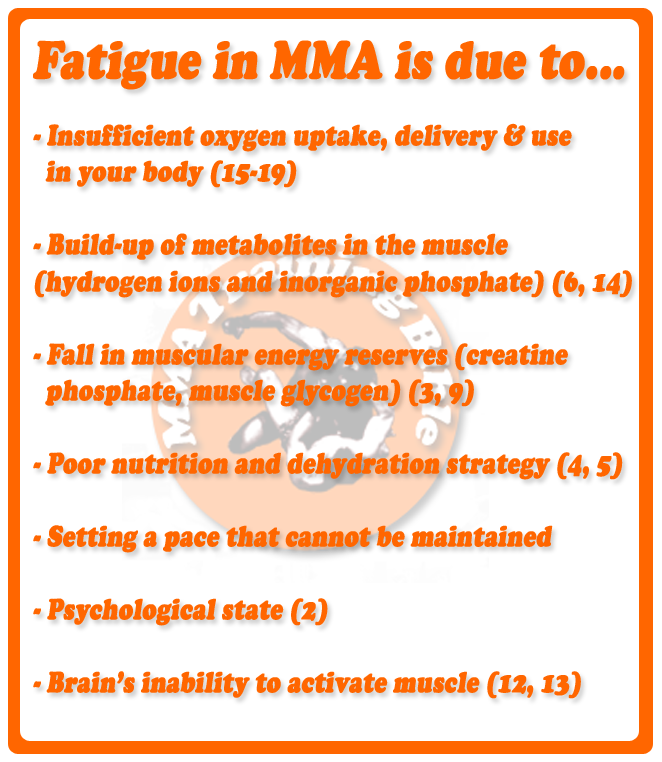

Fatigue in mixed martial arts (MMA) is unavoidable. It doesn’t matter how fit you are, your power output will fall as you perform repeated bursts of high intensity effort in the cage. This fatigue is most probably due to a combination of factors, including; insufficient oxygen uptake, delivery and use in your body (15-19), build-up of hydrogen ions and inorganic phosphate in your muscles (6, 14), a fall in muscle energy reserves i.e. creatine phosphate and muscle glycogen (3, 9), poor nutrition and hydration, with the latter primarily influenced by your weight cutting strategy (4, 5), your brain’s inability to activate your muscles (12, 13), your psychological state (2), and setting a pace that is too high and cannot be maintained. These factors are shown below in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Probable causes of fatigue in a typical MMA fight

After this kind of fatigue sets in, it takes a while to fully recover. For example, it can take up to 5-8 minutes of rest to resupply the creatine phosphate in your muscles (19, 20) and about 25 minutes to remove half of the lactate that builds-up (21, 22). Within a few hours of an intense training session your strength is mostly restored, and if you consume the right post-exercise meals, the glycogen in your muscles will be restored in short order. But depending on the intensity and type of workout that you completed, full tissue recovery can take up to a week (11). In most cases however, you will completely recover after a few days of rest and your body will be ready for another hard session.

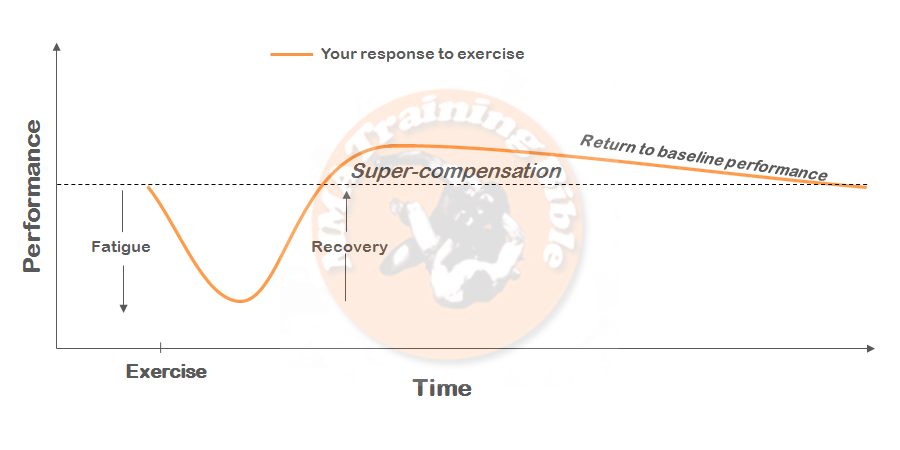

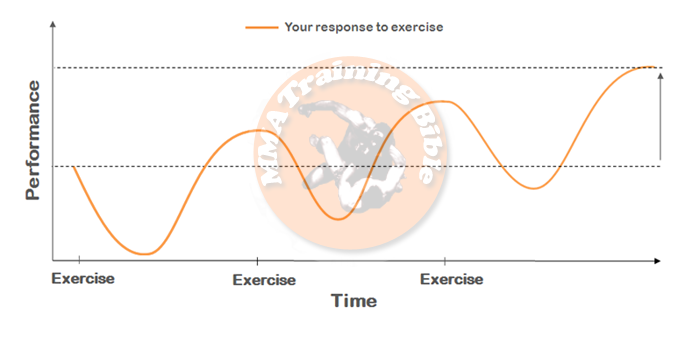

If you follow an appropriately designed training plan that incorporates the right amount of rest, your body will recover from this kind of training-related fatigue and over time you will grow stronger; this is called supercompensation. This whole process of training-fatigue-recovery-supercompensation is shown below in Fig 2. It is often called the training effect, although some call it ‘the general adaptation syndrome’ (1). No matter what you call it, you should understand it because it determines whether your body will respond optimally or sub-optimally to training. Take some time to study this figure because it’s really important. Reach out to me if you have any questions about Fig 2, because understanding it is critical to your success as a fighter.

Fig 2. Exercise is a stress that immediately causes fatigue and weakens you, but with enough rest you will recover and supercompensation will occur. But if you don’t exercise again, the supercompensation effect will dissipate and your performance will return to baseline (i.e. detraining will occur).

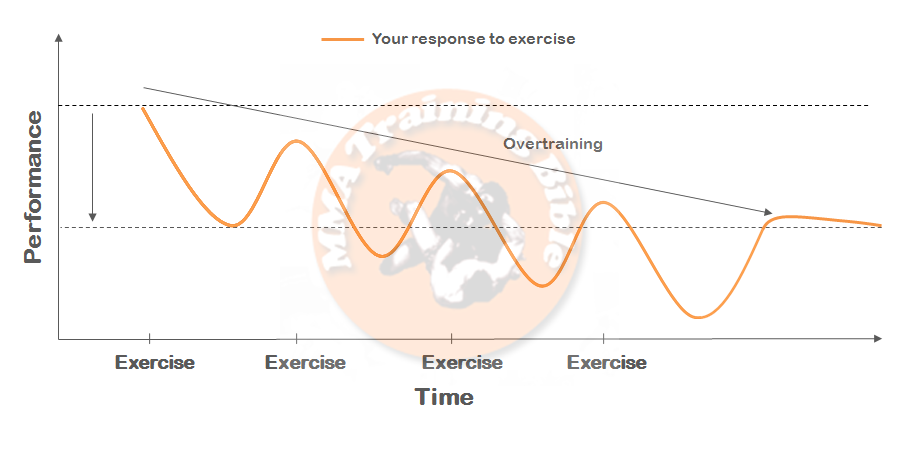

So, what happens if you don’t take sufficient rest between workouts and you use very high training volumes and intensities too often? The answer is simple; you will enter a state of overtraining. Think of it this way: your body always responds to the stress of training in the same way; first it fatigues and then it tries to recover. If you consistently avoid recovery your body will not undergo supercompensation and your performance will steadily decrease over time. This downward spiralling process of overtraining is shown below in Fig 3. Again, make sure to familiarise yourself with this figure; don’t be a victim of overtraining.

Fig 3. When you train too hard, too often, without sufficient rest between workouts, you don’t allow enough time to recover and your performance will steadily fall over time; this is overtraining.

Overtraining is very common in mixed martial arts because the sport demands a high degree of technical ability in multiple disciplines. Not only this, but fighters must develop a high degree of strength, power, agility, aerobic endurance and anaerobic endurance. Add in work, study, social and family commitments, and you have a perfect recipe for overtraining.

Understanding the training effect and how your body responds to training is the first step in avoiding overtraining. The second step is about recognizing the signs and symptoms of overtraining. This topic will be covered next in the second half of this article. We’ll also provide you with solid strategies to minimize your potential for overtraining and optimise your performance on fight day.

Part 2: Recognizing the signs and symptoms

Competing at a high level in mixed martial arts (MMA) is the end result of a successful long-term training plan administered over many years. Successful training plans strike a balance between training and recovery. However, this is particularly difficult in MMA because the sport requires technical proficiency in grappling and striking, not to mention a high degree of strength, power, agility, flexibility, and an/aerobic endurance. With so many performance factors to consider, fighters and coach often dedicate too much time to training at the expense of recover. This can lead to underrecovery and increase a fighter’s potential for overtraining. In a worst-case scenario, this can end a fighter’s career before it starts.

With a good understanding of how your body responds to the stress of training, you will better appreciate the concepts of underrecovery and overtraining; remember, knowledge is power! In the second half of this article you will learn about overtraining; what it is and how to recognize some of the more common signs and symptoms. You will also be provided with strategies to minimize your potential for overtraining. Ok, let’s dig into this topic.

What is overtraining?

First, it’s important to appreciate that whenever you train harder than usual, it is normal to experience a fatigue that lasts a few days and maybe even up to a week or so. This is an essential part of your training and it even has a name – it’s called overreaching (7). But when your fatigue doesn’t go away because you’re training too hard, too often and not taking enough recovery, you’ve reached a state of overtraining. This can take several weeks, months or even years to recover from (2).

There are two types of overtraining to be aware of. One is called sympathetic overtraining and the other is called parasympathetic overtraining (7). Whenever we use the terms ‘sympathetic’ and ‘parasympathetic’, we’re talking about your autonomic nervous system. This system is responsible for controlling things that happen automatically in your body, without thought, like your heart beat, breathing, sweating, or digestion.

There are two broad divisions of the automatic nervous system and you already know what they are because I’ve just mentioned them. One is the sympathetic division and the other is the parasympathetic division. It’s easy if you think about these systems as having opposing effects. For example, the sympathetic nervous system increases heart rate and the parasympathetic nervous system slows it down. Think of the sympathetic nervous system as a ‘quick response system’ that either gets you pumped up to fight, or to run away; that’s why some people use the phrase ‘fight or flight’ to describe it. On the other hand, think about the parasympathetic nervous system as a ‘dampening system’; it does things like increase digestion. That’s why some people use the phrase ‘rest and digest’ to describe it.

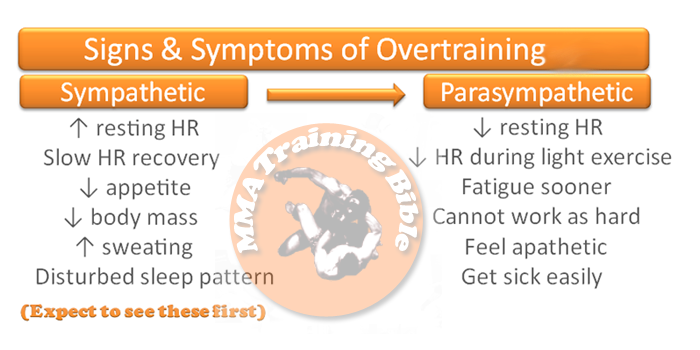

Given what you now know about these two branches of the autonomic nervous systems, I bet you can guess a lot of the signs and symptoms of sympathetic overtraining and parasympathetic overtraining. Sympathetic overtraining generally occurs first and is characterised by an increase in sympathetic activity during rest and exercise. With sympathetic overtraining, the signs and symptoms you need to watch out for include; an elevated resting heart rate (HR), a slow HR recovery after exercise, decreased appetite, loss of body mass, excessive sweating, and disturbed sleep pattern (1,7). These signs and symptoms are shown below in Fig. 4.

Fig 4. Signs and symptoms of sympathetic and parasympathetic overtraining

On the other side, parasympathetic overtraining generally occurs after sympathetic overtraining and is characterised by a decrease in sympathetic activity and an increase in parasympathetic activity. So with parasympathetic overtraining, the signs and symptoms that you need to watch out for include; a lower resting HR along with a lower HR during light exercise, you may also fatigue sooner and might not be able to work as hard. You might also notice yourself getting sick easily and often (1, 7). You may feel apathetic (having no interest, no feeling or no concern) or have a depressed mood, decreased self-esteem, emotional instability, restlessness, or irritability. Note that some of these psychological signs and symptoms may present with sympathetic overtraining as well. See Fig. 4 for a list of the signs and symptoms of parasympathetic overtraining.

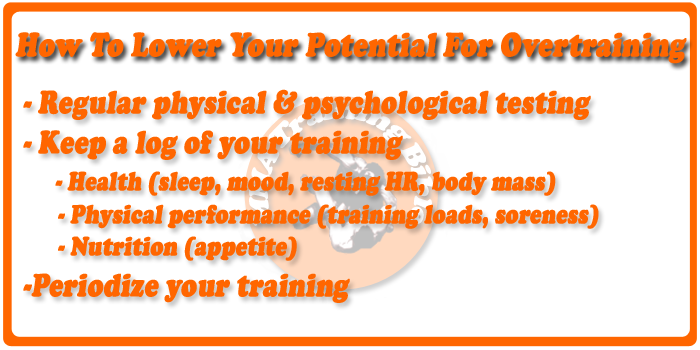

How to lessen your potential for underrecovery and overtraining

Unfortunately, Scientists have yet to find a reliable marker for monitoring overtraining. But don’t worry, there are some things you can do to lower your potential for underrecovery and overtraining. First, you’ve got to test yourself regularly using a physical and psychological testing battery. This will help you monitor your performance and your adaptation to training. Second, you should use a daily training log to monitor your health (sleep, mood, resting HR, body weight), physical performance (training loads, soreness, fatigue) and nutrition (appetite). The MMA Training Bible has provided you with an example template of a training log, download it for free here (Training log template).

Fig 5. How to lessen your potential for underrecovery and overtraining

Separate from regular testing and keeping a training log, one of the biggest factors that influence your potential for underrecovery and overtraining is the organization of your day-to-day training plan; this is also referred to as periodization.

Periodization is all about managing your fatigue during a long-term training plan. This is mainly achieved by altering your training volume and intensity over time, and balancing training with recovery. The goal of a periodized training plan is to progressively and systematically expose your body to greater levels of stress over time, while ensuring that you have enough recovery. If these stressors are timed properly your body will adapt, supercompensation will occur and your performance will steadily improve over time. This process of superior adaption is shown in below in Fig 6. This is what fighters and coaches in MMA need to be striving for.

Fig 6. By systematically altering the volume, intensity and frequency of your training over time (i.e. periodization), along with sufficient recovery, your body will adapt to training, supercompensation will occur and your performance will steadily improve. This is a superior adaptation to training.

Closing remarks

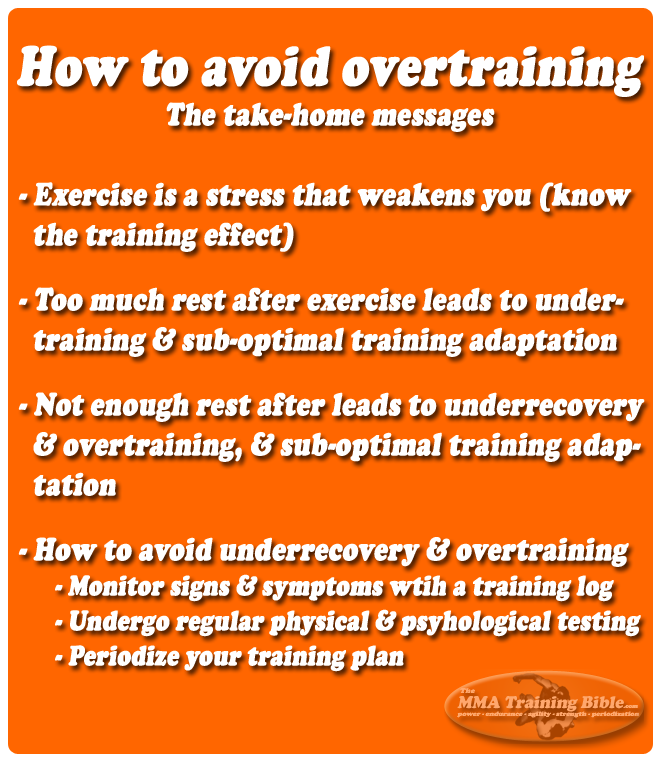

When you understand how your body responds to training and you monitor the signs and symptoms of overtraining, you can minimize your risk of overtraining. Use a training log to track some of the variables that may be related to overtraining. Periodization is particularly important in reducing your potential for overtraining because it helps you strike a balance between training and recovery, and this can help you optimize your adaptation to training. Remember, this superior adaptation is what you’re striving for; if you can get it right you’ll have the key to unlocking your full potential in the cage. If you get it wrong, it’s a career killer.

You can review the take-home messages from this article on overtraining in Fig 7.

Fig 7. Take-home messages from this article

If you’re interested in creating a training program to optimize your performance on fight day whilst minimizing your chances for overtraining, take a look at some of the online video training courses offered by Dr Jason Gillis and the MMA Training Bible.

Check your understanding of this article series on overtraining by answering these questions

- Name some of the factors that cause a fighter to fatigue in a typical MMA fight.

- How does your body respond to the stress of training? (use a diagram in your explanation)

- What is the difference between overreaching and overtraining?

- Name a few differences between sympathetic and parasympathetic overtraining.

- How can you lower your potential for overtraining?

If you found this article useful, so too might your training partners – please share!

References and further study

- Bompa & Haff Periodization Theory and Methodology of Training 5th ed Champaign ILL USA (2009)

- Borg (2007) On perceived exertion and its measurement Doctoral Thesis. Stockholm University.

- Burgomaster et al., J Appl Physiol 100:2041-2047 (2006)

- Costil et al., Am J Clin Nutr 34:1831-1836 (1981)

- Coyle, J Sports Sci 9:29-51 (1991)

- Dutka & Lamb J Physiol 560: 451-68 (2004)

- Fry & Kraemer Sports Med 23:106-129 (1997)

- Hultman et al., Scand J Clin Lab Invest 19:56-66 (1967)

- Karlsson et al., J Appl Physiol 33:199-203 (1972)

- Mccann et al., Med Sci Sports Exerc 27:378-389 (1995)

- Nicol et al., Sports Med 36:977-999 (2006)

- Nybo & Nielsen J Appl Physiol 91:2017-2023 (2001)

- Ross et al., Sports Med 31:409-25 (2001)

- Westerbalad et al., News Physiol Sci 17:17-21 (2002)

- Rampinini et al., Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 34:1048-54 (2010)

- Bishop & Spencer J Sports Med Phys Fitness 44:1-7 (2004)

- Bishop et al., Eur J Appl Pysiol 92:540-7 (2004)

- McMahon & Wenger J Sci Med Sport 1(4):219-27 (1998)

- Tomlin & Wenger Sports Med 31:1-11 (2001)

- Bogdanis et al., J Physiol 482:467-80 (1995)

- Kreamer WJ, Fleck SJ, Deschenes MR. (2012). Exercise Physiology: Integrating Theory and Application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkin: China.

- Plowman SA, Smith DL. (2011). Exercise Physiology: For Health, Fitness, and Performance (3rd ed.). China: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Leave a Reply