Dive into the essence of optimal fight preparation with Part 2 of the MMA Training Bible’s series on periodization, masterfully detailed by Dr. Jason Gillis. This comprehensive guide breaks down your fight schedule into strategic phases, each designed to enhance performance, manage fatigue, and peak at the right moment. From establishing a strong physical base in the general preparation phase to refining fight-specific skills and culminating in a carefully timed taper, this article offers a blueprint for fighters to avoid overtraining and maximize their potential. It’s an invaluable resource for anyone looking to elevate their MMA game, blending the art and science of training periodization to ensure you’re fight-ready when it matters most.

Welcome to part 2 of the MMA Training Bible’s article series on periodization. In the last article you learned that periodization is simply the process of organizing your training in a way that helps you to manage your fatigue on a daily, weekly and monthly basis. You also learned that periodization is an art, but it’s also a science, and if used correctly, it can help you lower your potential for over-training and optimizing your performance on fight day.

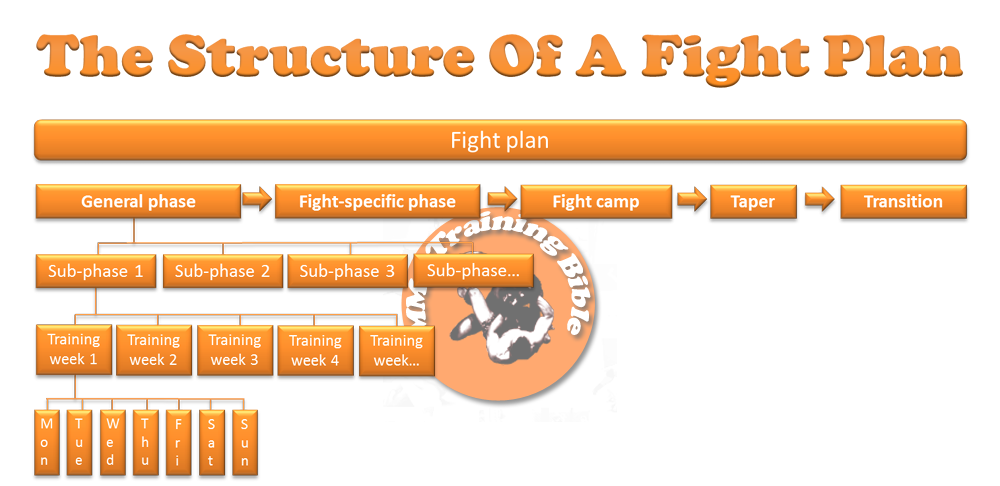

In the last article, I also showed you what a periodized fight schedule looks like. Here it is again:

In this article, we’re going to break down the structure of this fight schedule. The first thing to notice about the fight plan is that it’s divided into a number of large phases, each of which is further divided into smaller sub-phases that are carefully sequenced to help you manage your fatigue on a monthly basis. Each sub-phase is further divided into training weeks, which help you manage your fatigue on a weekly basis. Training weeks are further divided into training days, which can be further divided into any number of training sessions.

You’re always going to structure your fight plan into a few large phases, no matter how many times you fight in one year, they are:

- The general preparation phase

- The fight-specific preparation phase

- The fight camp

- The taper

- The transition

Each phase has very specific objectives. Let’s take a deeper look at each of these phases.

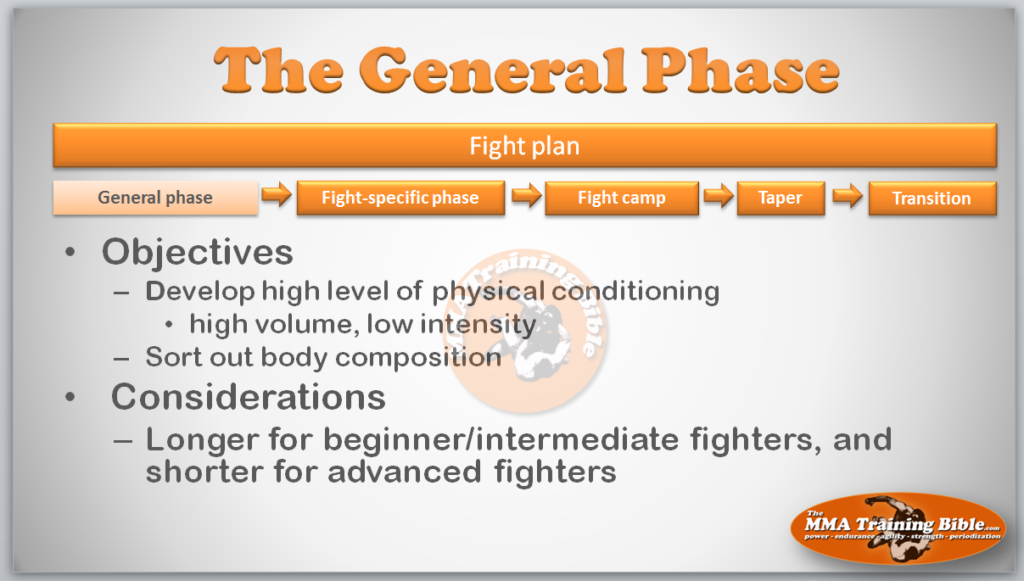

General preparation phase

The main objective of the general preparation phase is to establish a high level of physical conditioning by using large volumes of general and non-specific MMA activities. This should include the development of high intensity aerobic endurance and a foundation of strength in a wide variety of activities (1, 3).

Any needed changes in body composition should also be addressed during this phase (2). The general preparation phase should be longer for beginner and intermediate fighters, and shorter for more advanced fighters (in some special cases, it can be eliminated altogether). Because the main emphasis is on increasing training volume, your level of fatigue will increase, so competitions should not be scheduled in this phase (1).

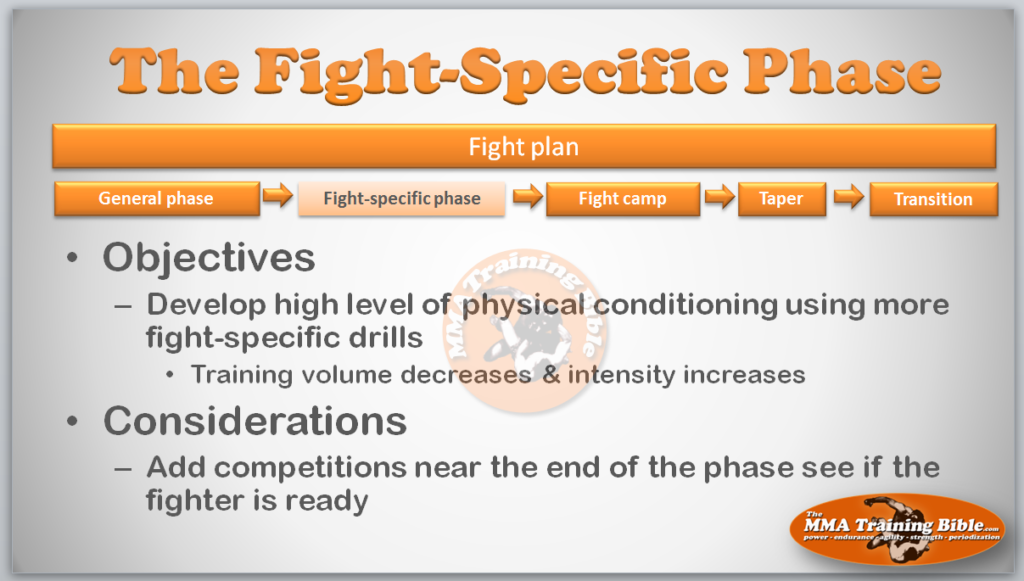

Fight-specific preparation phase

Like the general preparation phase, the fight-specific phase aims to improve aerobic endurance and strength, but rather than using general exercises like running, cycling or rowing to achieve this, more fight-specific drills are incorporated. Training volume decreases throughout this phase, which allows for a gradual increase in training intensity (1, 3). About mid-way through this phase, training intensity may surpass volume (2).

As your training becomes more specific to MMA, you become more prepared to fight. In the later part of this phase, competitions can be used to provide feedback about a fighter’s exact level of preparedness, but competitions should only be entered when the fighter is capable of achieving their most important training objectives. If you’re going to do this, competitions and opponents should progressively increase in difficulty as the main fight gets closer. You’ve got to be careful to minimize the risk of injury when you’re entering heavy contact competitions during this phase. If you don’t want to, then non-contact submission wrestling/jiu-jitsu or boxing/kick-boxing competitions with protective gear might be a good idea. As an alternative to official inter-clubs and competitions, a coach can also scheduling team training sessions with other local gyms.

Both the general and fight-specific preparation phases are probably the most important because they establish your physical, technical, and psychological base for the fight camp. If you skip either one, or they are inappropriately designed, your ability to tolerate high intensity training during the fight camp will be compromise, along with your fighting performance.

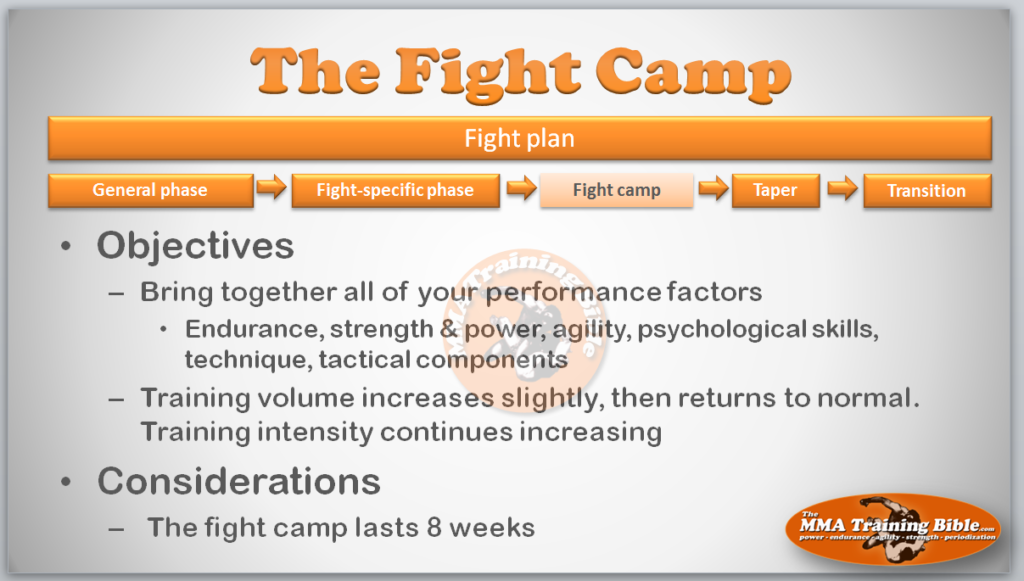

Fight camp

The main goal of the fight camp is to bring together all of the performance factors that the fighter needs to compete successfully. At this stage the fighter should be focusing on psychological training and perfecting specific techniques and tactics that will be used in the fight.

At the beginning of the fight camp, training volume increases for a short period, followed by a return to normal training volumes. This increase in training volume at the beginning of the fight camp allows the fighter to place a greater emphasis on fight specific technical and tactical preparation (1). This period of concentrated loading is placed at the beginning of the fight camp, approximately eight to 10 weeks before the fight, because some research has shown that training adaptations from very intense periods may take many weeks to present (4). Training intensity continues to increase throughout the remainder of the fight camp, reaching its highest level two to three weeks prior to a fight.

Taper

In the last 8 to 14 days before your fight, a taper or unloading period should be used (5). The goal of a taper is to optimize your performance in the cage. This is achieved by reducing training volume while maintaining intensity for two weeks before your fight.

The number of weekly training sessions should fall by about 20 % (two out of 10, or one out of five training sessions) (1). Now, here is the important thing: because your fatigue recovers faster than your fitness is lost from detraining, a taper will result in a performance improvement; this is what a peak is (5). With all of this extra rest, you’ll feel a greater sense of vigor, your mood will improve, and your sense of fatigue and perception of effort in everything that you do will fall (1, 5). This is how you peak for a fight, or anything else, it’s a similar process across all sports. The taper is also the period when you implement any special preparations, such as a weight cutting strategy, or specific training, such as targeting relaxation, confidence building and motivation, or review last minute tactical elements.

Transition

After your fight, a three to six week transition phase is necessary to remove the accumulated physiological and psychological fatigue that developed during the past few months of training (1).

This phase is not an off-season, because fighters do not have an off-season, it’s a transition from one fight plan to the next. This period must feature activity, or else detraining will occur. You can avoid this by using primarily low intensity activity (2) and active rest with minimal technical or tactical focus. If you do this right, you can minimize detraining and carry some of your physical adaptations from the last training plan into the next training plan (1). But before you start a new fight plan, you should be fully recovered from the last one. If a new fight plan is initiated without full recovery, performance will be impaired in future fights, and your risk of injury will increase.

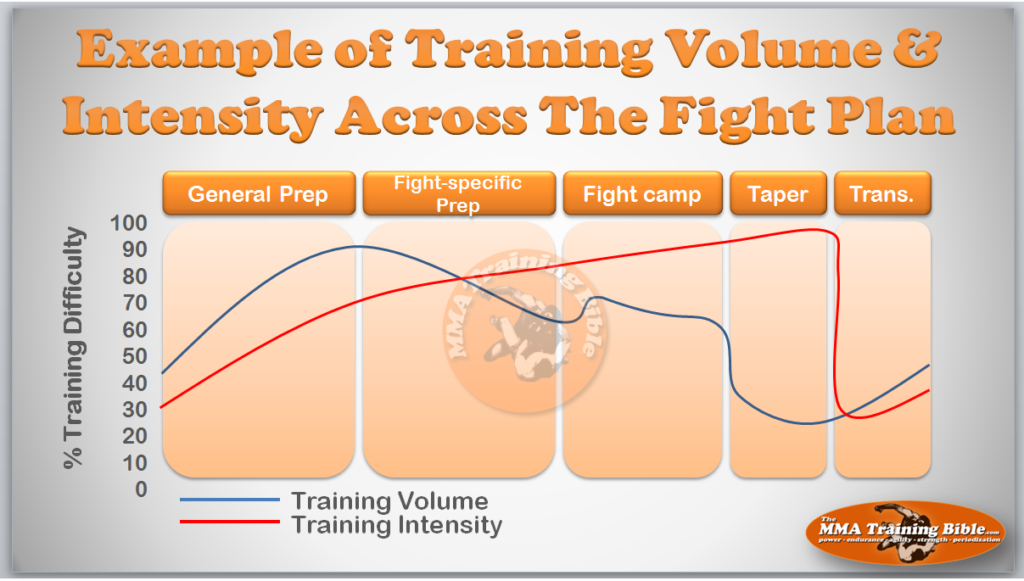

Just to make things a little more clear for you, I’ve put together a figure showing how your training volume and intensity should change across a fight plan.

If you’re interested in this article series or other great topics from The MMA Training Bible, please sign up to our email list at the bottom of the page and you’ll get an email whenever we post a new article. Also, don’t forget to share this article with your training partners. You may also be interested in our FREE online training program on Bioenergetics, which touches on periodization for MMA.

I hope you enjoyed this article and found it useful, stay tuned for the next one – and don’t be afraid to ask questions; this stuff can be a little confusing!

Be sure to check out the next article in the series: Read Part 3 here.

Sincerely,

Dr. Jason Gillis

Take home messages

So that is an overview of how and why the MMA Training Bible structures its plan the way it does.

In this article you learned all about the big phases of the fight plan; the general prep phase, the fight-specific phase, the fight camp, the taper, and the transition. You learned that if you arrange your training in this way, you can avoid overtraining, dissipate your fatigue, and cause a peak in your performance for your fight. And you learned how training volume and training intensity should change across your fight plan.

Stay tuned in for the next article in the series on sequencing your training sub-phases.

References and further study

Leave a Reply