MMA is a sport that demands a high degree of flexibility. Flexible fighters can perform a wider range of techniques, both offensive and defensive, than less flexible fighters. These fighters will have a clear advantage on fight day. We all know this, but there is only so much training time available during the week, and although flexibility is important, it often takes a back seat to other types of training.

We here at The MMA Training Bible feel that flexibility is important, but we also appreciate that fighters and coaches have time constraints, so we’ve set our sights on identifying the minimum amount of stretching that is required to improve flexibility.

We’ll do this by using scientific research. We believe that understanding a little bit of Science is a good thing. It empowers fighters and coaches and helps them see through bullshit. For this reason, we’ll talk about the Science of flexibility in the first half of the article, and then we’ll give you a practical example in the second half, so stick with us and all will be revealed.

The Science of Flexibility

Flexibility is defined as the ability to move a joint, like your shoulder or knee, through its complete range of motion (ROM). Flexibility is influenced by the ‘stiffness’ of the muscles surrounding the joint and a few other factors like the tightness of ligaments (attach bone to bone) and tendons (attach muscle to bone) surrounding the joint, it may even be influenced by your body temperature(2).

Lots of studies have shown that stretching can improve flexibility; but strangely, Scientists don’t really know why. It could be due to a decrease in the stiffness of muscles (perceived or actual), an increase in muscle length, or some combination of each(2).

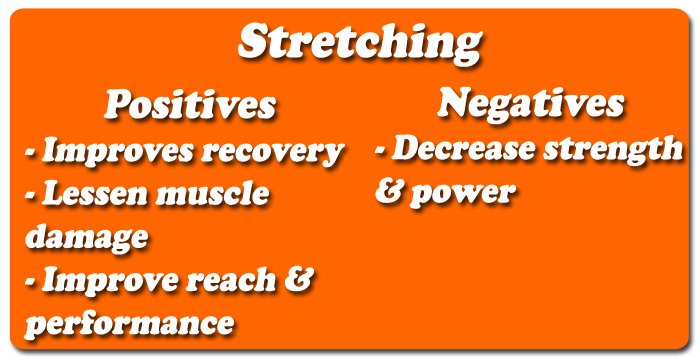

Regardless of the cause, flexibility can be improved with long-term stretching, but there are both positive and negative consequences of stretching. On the negative side, stretching, when undertaken immediately before exercise, has the effect of impairing performance. Specifically, the immediate changes in muscle compliance that occur with stretching can affect the length-tension relationship of muscles (4). Translated into English, this means that stretching before exercise, especially static stretching (when you hold a stretch), may impair your strength and power output. Because of this, static stretching should not be performed with any intensity prior to strength, high speed, explosive or reactive activities (4). Dynamic stretching (like swinging your arm) is perhaps more appropriate prior to these types of exercise.

On the positive side, long-term stretching programs that improve flexibility have also been shown to lessen muscle damage and promote recovery from exercise(3) and improving your flexibility will probably improve your athletic performance because it enhances your ability to stretch or reach in sport(4). The MMA Training Bible performed a detailed review of the most relevant scientific literature with the hopes of identifying the minimal amount of static stretching effort required to maximise your flexibility.

There is one other stretching method that is more effective than static stretching for improving flexibility – It’s called PNF (Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation). We don’t cover it here, as it’s a bit complex, but if you want to learn how to do it, watch our free lecture on warm-ups and flexibility here. Below we’ll be discussing static stretching, as it’s pretty easy for most people to do, so read on to learn more.

Using this evidence-based approach, we identified a number of studies showing that a long-term stretching program undertaken separately from regular training can increase flexibility (5-9). After carefully analysing each of the studies, we identified the minimal amount of effort that is required to see a significant improvement in joint range of motion (i.e. flexibility at a joint).

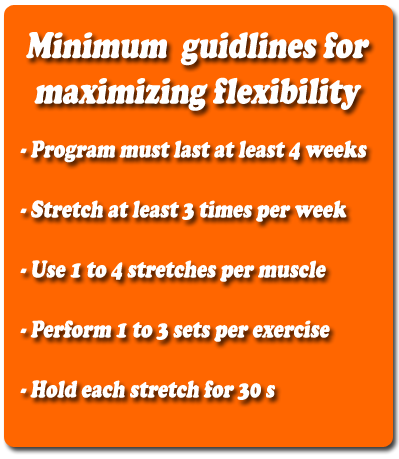

Our work indicates that a static stretching program undertaken for a minimum of 4 weeks(6-8) can result in significant gains in flexibility (from 5 to 16 degrees of joint range of motion [7,8)]), so long as it is undertaken on at least 3 to 5 days per week (5-7,9), with each static stretch being held to a maximal tolerable limit for 30 seconds (5-7), over 1 to 3 sets (5, 7-9), with 1 to 4 stretching exercises performed for each muscle group (7).

Below we’ll review a basic workout that can improve flexibility, but if you want to learn how to incorporate this routine into a whole training program that builds all of the key performance factors required in MMA (strength, power, endurance, etc.,), check our our whole course on the Science of MMA, here, or on our YouTube Channel.

Example stretching program

Ok, it’s time to apply everything we’ve learned up to now. I want to give you an example of a program that I designed for a fighter a few years back. The main of this program was to improve lower body joint range of motion, particularly around the hips, to enable the fighter to perform a wider range of techniques, particularly the high kick.

As a side note, before you start any new training plan, you should always take some baseline measures before you start and every 6 to 12 weeks thereafter. If you don’t, how else will you know if the program is actually working? You can use the same tests that I did with this fighter – read this article for more information, or check out this video.

After you take baseline measures, you’re ready to start the stretching program. You should aim to complete a minimum of 3 sessions per week. Ideally these sessions should not be completed before one of your other training sessions. Also, make sure you’re warmed up before you start stretching. Here is a sample warm-up, but feel free to adapt it to suit your needs.

Warm-up prior to beginning the stretching session

- Dress warm to stay warm after the warm-up, but your movement should not be restricted by your clothing.

- Undertake light whole-body exercise until you begin sweating (i.e. running/jog, cross-trainer, or rowing machine).

- Perform the following dynamic stretches, but do not approach full range of motion.

- 30 seconds of arm-swings front to back and side to the side (change direction)

- 30 seconds of hip circles, change direction half way.

- 30 seconds of leg-swings front to back and to the side.

The stretching program Perform the following stretches (see image gallery below). Hold each stretch to a maximal tolerable point, but you should not experience pain, and be sure to follow the instructions in the image.

Ok, that’s it. I hope you got some use out of this post. I’d love to provide you with stretching programs for every joint, but there’s not enough time in the day. It’s up to you to figure out what muscle groups that you need to stretch, and the exercises, I’ve provided you with the rest; the program details.

Ok, that’s it. I hope you got some use out of this post. I’d love to provide you with stretching programs for every joint, but there’s not enough time in the day. It’s up to you to figure out what muscle groups that you need to stretch, and the exercises, I’ve provided you with the rest; the program details.

I’d love to hear your feedback on this post, so please leave a comment, and if you’ve found the article useful, share it with your friends and training partners.

Best,

Dr. Jason Gillis

References

- Thompson, Gordon & Pescatello (2010) In: Edited by Thompson, Gordon, Pescatello, (8th ed.) (p.60 to 104). Baltimore, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Weppler, Magnusson (2010) Physical Therapy, 90(3), 438-449.

- Chen et al. (2011) Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(3), 491-500.

- Behm & Chaouachi (2011). European Journal of Applied Physiology, 11, 2633-2651.

- Bandy, Irion & Briggler (1997) Physical Therapy, 77(10), 1090-1096.

- Higgs & Winter (2009) The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(5), 1442-1447.

- Marshall, Cashman & Cheema (2011) Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 14, 535-540.

- Nakamura et al (2011) European Journal of Applied Physiology, DOI 10.1007/s00421-011-2250-3.

- Roberts & Wilson (1999) British Journal of Sports Medicine, 33, 259-263.

Leave a Reply